Award winning design does not necessarily translate to an effective, successful or liveable built environment. My interest and passion for interesting design is somewhat tempered by my having seen the consequences of projects not matching constructability and coordination with interesting design. As I have previously revealed obliquely in my post on How to Pick a Lawyer, I am a junky for interesting technology, construction and design. I still think that instead of art for arts sake, our building environment is our living environment and at its best, design and construction integrate these two potentially disparate arenas.

Award winning design does not necessarily translate to an effective, successful or liveable built environment. My interest and passion for interesting design is somewhat tempered by my having seen the consequences of projects not matching constructability and coordination with interesting design. As I have previously revealed obliquely in my post on How to Pick a Lawyer, I am a junky for interesting technology, construction and design. I still think that instead of art for arts sake, our building environment is our living environment and at its best, design and construction integrate these two potentially disparate arenas.

I have spent a career of construction litigation crossing boundaries in the industry. I cut my teeth defending design professionals, but I have since represented contractors and subcontractors. I have worked with owners and product manufacturers. Each camp has its own shorthand description of the failures of others. I have heard the constant grumblings of the inability of contractors to follow the plans and specifications (or at worst even read them). On the other side, I have heard contractors complain that architects draw pretty pictures but are clueless about how to put buildings together. I have seen examples where each criticism was fair and others where they were totally unwarranted.

Placing all this in the context of the end user, I have lived the first hand experience of a train wreck between architecture as high design versus and living in the end product. I attended Yale University and lived on campus in the Morse College dorm my sophmore year. When most people think Yale, they envision the gothic style architecture which dominates the campus and is ably represented by the imposing shot of Harkness Tower to the above. Morse College is a little different … designed in a distinctly modern style by architect Eero Saarinen.

Placing all this in the context of the end user, I have lived the first hand experience of a train wreck between architecture as high design versus and living in the end product. I attended Yale University and lived on campus in the Morse College dorm my sophmore year. When most people think Yale, they envision the gothic style architecture which dominates the campus and is ably represented by the imposing shot of Harkness Tower to the above. Morse College is a little different … designed in a distinctly modern style by architect Eero Saarinen.

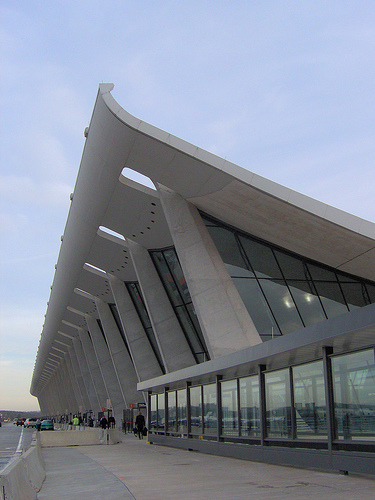

I was open on some level to Saarinen’s style. I grew up with his Dulles Airport design in Northern Virginia and loved that project with its suggestion of a sweeping plane’s wing in the terminal. Morse College was a little different. Try living in spaces with literally no right angles in the living areas (which can be seen easily here where there are floor plans for Stiles and Morse Colleges). As Wikipedia pithily states, “This resulted, notoriously, in two rooms which have eleven walls, none of which is long enough to put the bed against and still be able to open the door.”

The lack of right angles was a physical impediment that ranged from a mere minor annoyance to a constant source of fury depending on how your room lottery worked out. Luckily, our group drew well and my cozy single was pretty workable. The more complex aspect of preparing to live in Morse College was based in social structure. For every other dorm, planning for living arrangements basically called for grouping off in pairs. Sets of best friends could group up into fours for lotteries. There might be an odd person out here or there, but the numerical structure basically fit typical social conventions.

The lack of right angles was a physical impediment that ranged from a mere minor annoyance to a constant source of fury depending on how your room lottery worked out. Luckily, our group drew well and my cozy single was pretty workable. The more complex aspect of preparing to live in Morse College was based in social structure. For every other dorm, planning for living arrangements basically called for grouping off in pairs. Sets of best friends could group up into fours for lotteries. There might be an odd person out here or there, but the numerical structure basically fit typical social conventions.

Not so with Morse. The numerical structure of the rooms was as completely incongruous as the walls. Instead of pairs forming groups of four, most room bidding centered around bizarre troups of sevens matching up with other sevens. Every year, the politics around room assignments were a bloody nightmare of hurt feelings and betrayals. Reaching up the elder food chain (and while I started in 1984, I had friends who dated back to the 1970’s), I was informed that this bitter history was constant and consistently repeated each year.

Now that I litigate construction and design issues on a constant basis, I often find myself relearning the experience of living architecture first hand. I am fascinated by the tension between celebrated design and practical performance. I love the aesthetic of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water, but I will admit to a chuckle regarding the near constant structural, mold and water problems at Falling Water.

Now that I litigate construction and design issues on a constant basis, I often find myself relearning the experience of living architecture first hand. I am fascinated by the tension between celebrated design and practical performance. I love the aesthetic of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water, but I will admit to a chuckle regarding the near constant structural, mold and water problems at Falling Water.

The best projects are those which marry both art and application. The most successful projects are those where the architects embody the master builder concept rather than the smug artiste, where the contractors are not only master craftsman but knowledgeable about design and helping with coordination. It is perhaps utopian to expect everyone to pull the oars in the same direction, but when there are shared values, relationships and mutual respect, it can produce tremendous results in the built environment.

(Credit or blame for encouraging this post should go to my pal Laurie Meisel, social media presence for Architectural Record and Green Source Magazine, amongst other endeavors)

Images:

Harkness Tower by wallyg

Eero Saarinen Dulles Airpor by XYZ+T

Morse College Renovation by Phil Handler

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water by Figuura